Observers supported Adesina’s view, noting that while such loans provide developing countries with the financing they need, they can be expensive and subject to fluctuations in commodity prices, making repayment difficult.

Known as the “Angola model”, the financing concept provided billions of reconstruction dollars from Chinese lenders to Luanda two decades ago, when the West was unwilling to fund projects after 27 years of civil war in the oil-rich country.

Angola secured about $24 billion from the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank (CDB) between 2004 and 2016 to finance infrastructure, ranging from schools and hospitals to roads and power transmission networks.

The model, which used Luanda’s oil revenues as collateral for the loans, worked well until 2014, when oil prices fell and Angola was forced to pump more of its reserves to pay off debts.

Yun Sun, co-director of the East Asia Program and director of the China Program at the Washington-based Stimson Center, said the Covid-19 pandemic and its economic impact have severely damaged the ability of African countries to service their debts.

“Although the resource-backed loans did not generate economic benefits to repay the loans, debts and interest continued to accrue. The loan relied on a highly risky model to be viable and when it is not viable, borrowers are in big trouble,” Sun said.

Angolan President Joao Lourenco acknowledged in 2019 that the concept behind oil-backed loans was not working and said his country was discontinuing the practice as “advised by the IMF and the World Bank”.

How China and Angola are redefining ties for a post-oil, post-loan era

How China and Angola are redefining ties for a post-oil, post-loan era

On a visit to China in March, Lourenco secured a debt relief deal that will see Angola pay between $150 million and $200 million less per month to repay its CDB loans.

A 2020 Natural Resource Governance Institute study found that several countries in sub-Saharan Africa have borrowed at least $66 billion in loans backed by foreign financing since 2004, more than half from CBD and China Eximbank.

Gyude Moore, a policy fellow at the Washington-based Center for Global Development and a former public works minister in Liberia, said “there are questions about the opacity and the difficulty of resolving those loans in times of debt problems.”

He said that while African sovereign states were free to enter into loan agreements, the IMF drew on global public resources to respond when approached to intervene in times of debt problems.

“This makes the accumulation of sovereign debt a global development problem. The difficulty African economies have faced in securing relief from either [the Debt Service Suspension Initiative] or the Common Framework makes opaque debt obligations unpalatable.”

IMF report says Chinese loans are not the main debt burden in sub-Saharan Africa

IMF report says Chinese loans are not the main debt burden in sub-Saharan Africa

Moore, who noted that China recently granted a $400 million loan to Niger through the China National Petroleum Corporation, said that even on the most generous definition of success “we would be hard-pressed to find an African case where such loans were made.” successful”.

He said South Sudan was struggling to repay a similar oil-backed loan, resorting to using wages to service it, Zimbabwe discussed handing over assets to pay a private creditor, while Chad’s debt burden with European commodities trader Glencore it took years to resolve.

In another example, Moore said the Democratic Republic of Congo – the world’s largest cobalt producer – “has repeatedly accused China of not holding up its end of a resource-backed deal.”

DRC President Felix Tshisekedi has pushed for a review of multibillion-dollar deals he said were “poorly negotiated” under his predecessor Joseph Kabila, raising the issue during his visit to China last year.

Relief as Chinese company reaches royalty deal on Congo cobalt mine

Relief as Chinese company reaches royalty deal on Congo cobalt mine

In a renegotiated deal on copper and cobalt joint venture Sicomines, Sinohydro Corp and China Railway Group agreed to invest up to $7 billion in infrastructure, up from $3 billion previously agreed in the infrastructure minerals deal.

International project finance lawyer Kanyi Lui, partner and head of China at multinational law firm Pinsent Masons, said resource-backed lending was once the purview of European commodity traders and lenders.

They were widely used when Chinese politics and trade entered the market in the 2000s, but began to take on a darker tone in Chad’s oil-for-money deal with Glencore in 2013 and 2014, according to Lui.

The deal with Chad ran into difficulties almost immediately and had to be restructured in 2015 following a slump in global oil prices. Rising interest payments meant the debt consumed almost all of the country’s main source of revenue, prompting further negotiations.

The IMF and the World Bank must do more to defuse the debt bomb of poor countries

The IMF and the World Bank must do more to defuse the debt bomb of poor countries

Lui said Asian lenders, including those from China, tended to offer more predictable and stable terms for resource-backed loans (RBLs) compared to other players. “Overall, Chinese RBLs are a positive force in Africa.”

According to Lui, research has shown that Chinese and other Asian lenders of asset-backed loans tend to charge interest rates between 0.5 and 3 percent a year.

“Chinese RBLs are also almost always provided in connection with infrastructure construction, which addresses one of the main risk areas of RBLs and helps the borrowing country develop its economy and repayment capacity,” he said.

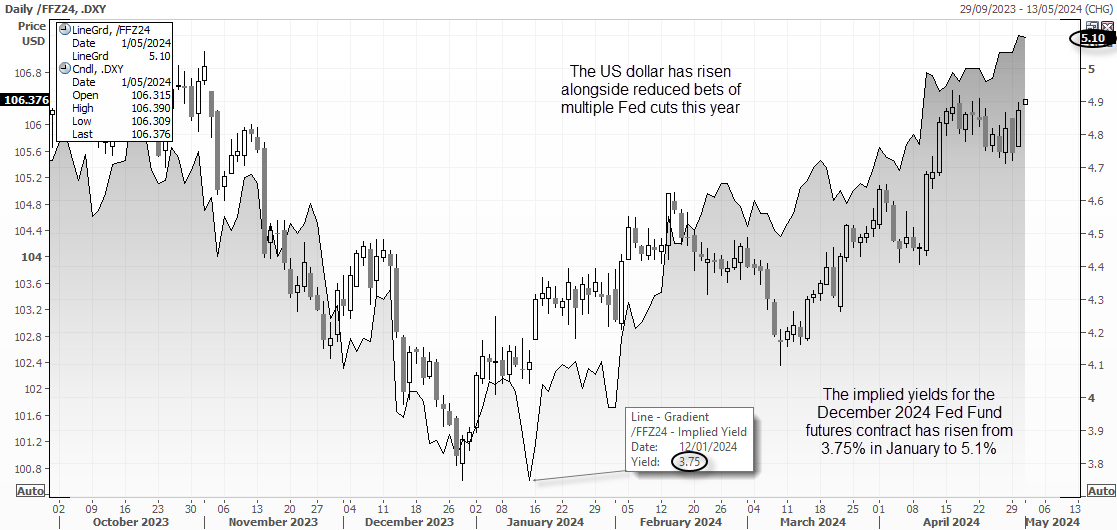

But fluctuations in U.S. commodity prices and interest rates are causing a shift away from such loans, according to Lui.

The West is racing to challenge China’s dominance of the African mineral market

The West is racing to challenge China’s dominance of the African mineral market

Resource-rich countries around the world are beginning to adopt a value-added approach to processing their raw materials. By requiring these services to be performed domestically, the model helped the local economy and helped boost the skills of its workforce, he said.

“A great example is how Indonesia and Chinese companies have come together very successfully in recent years to promote the establishment of integrated stainless steel and electric vehicle battery mining, refining, manufacturing and export projects,” Lui said.

Zhou Yuyuan, deputy director of the Center for West Asian and African Studies at the Shanghai Institutes of International Studies, said resource-backed loans provided urgently needed countries with the support they needed for development.

“In the cases of Angola and the DRC, the oil and minerals for infrastructure development agreements have played an important role in promoting infrastructure development and economic growth in both countries,” he said.

According to Zhou, the resource-backed lending model in Angola and the DRC has been generally successful, despite the economic pressure it can cause on borrowing countries when prices fall.

“There is no denying the important role of this model in promoting infrastructure and national development in both countries because of the current debt problem,” he said.

“Just as other countries also have debt problems, building infrastructure will inevitably lead to an increase in debt. But as patient capital, its important role in supporting future economic development must be seen holistically.”

#Chinas #oilforinfrastructure #loan #model #Africa #rethought