image source, You will do Sevenzo

Sylvia Dhliwayo, an expert at climbing the hurdles of Zimbabwe’s struggling economy and trading the many currencies at stake, is upset.

She works hard every day to send her four children to school. Waking up at 04:00 most mornings, he heads to Mbare Main Market in the capital, Harare, to buy maize, groundnuts, doughnuts, eggs and buns to sell at his neighborhood street stall.

From tomatoes to avocados, pots to second-hand clothes, Mbare is a trading hub and traders there set the prices, which change daily in the fluctuating economy.

What has angered Dhliwayo and other traders is the government’s latest move to introduce a new local currency.

- author, You will do Sevenzo

- Paper, Harare

“They didn’t give us any warning. We saved and saved their useless money and overnight the notes are worthless”, she tells me exasperated.

Known as the Zig, which means “Zimbabwe gold”, it was introduced a month ago and replaces the RTGS digital currency and cash “bonds”.

The measure is supposed to help fight inflation and hyperinflation, a disease that has plagued Zimbabwe for the past two decades. This led the government to abolish the Zimbabwe dollar in 2009 and since then most people have been using the US dollar.

Just before the Zig was launched, you could buy a packet of peanuts from Ms Dhliwayo for $0.50 (£0.40) or $2,500 worth of bond notes.

But when Reserve Bank governor John Mushayavhanu gave Zimbabweans three weeks to exchange their bonds, they immediately lost what little value they had: the peanut bag soared to Z$40,000, although by then Dhliwayo was only accepting the payment in US dollars.

Much to Ms Dhliwayo’s exasperation, she is still only trading in US dollars.

Merchants like to use the local currency to give change to customers since there is a shortage of US coins. Supermarkets often choose to change the lollipops.

Ms Dhliwayo would use Zigs if there was one, but it exists mostly digitally and in a place where people can rarely charge their phones because of blackouts, money counts.

“The new money is not available yet, it’s just in people’s phones and bank accounts. Everything, absolutely everything, is still in US dollars.”

image source, Getty Images

Mushayavhanu took a defiant stance in early April when introducing the gold-backed currency, saying it was done on the advice of the World Bank.

“If you’re going to blame me, you’re actually blaming the World Bank,” he said, urging Zimbabweans fed up with seeing their money disappear overnight to be patient.

“Maybe they didn’t advise us properly. And if they didn’t advise us correctly, that’s fine. Let’s refine it.”

But given that this is the sixth time the local currency has changed hands in 20 years, Zimbabweans’ lack of confidence is understandable.

The Zimbabwean dollar, whose highest denomination at one time was Z$100 trillion, was transformed into bearer cheques, farm cheques, RTGS and bonds.

A local independent Sunday newspaper, The Standard, lamented the lack of publicity for the sudden currency switch to Zigs, as phone companies, supermarkets and public transport stopped accepting the previous incarnation, the bonds, as legal tender.

Tourists have been unable to make Visa payments as uncertainty over the true value of the Zig has made their cards unusable while the recalibration continues.

“If the Zig does not go the same way as the RTGS, bearer cheques, agricultural checks and bonds that preceded it, then it would be a boon to Zimbabweans who in the past saw all their savings wiped out by inflation,” he surmised. the publisher of the newspaper.

However, you can see why companies are reluctant to deal with it.

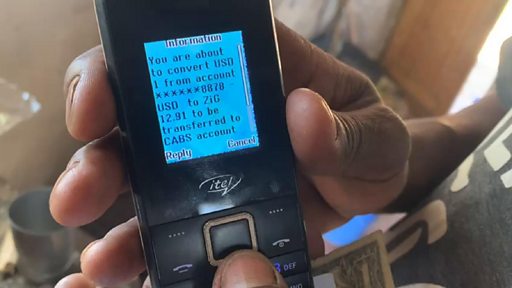

A gardener working in South Harare showed me on Friday morning that he was being offered 12.91 Zig to $1 in his phone bank account, even though he thought the street price was 13.50 Zig to $1. A couple of hours later, a second-hand clothing seller on the road said he was trading 15 Zig for $1.

For Maxwell Gombe, who makes his living by selling old bills of billions and trillions of dollars, souvenirs of the economic crisis, to tourists who visit the country’s places of splendor, it is all business as usual.

“American dollars for old notes… 500,000; millions; trillions,” he shouts through his high-pitched hailer in Harare, where he buys the old notes to sell in Victoria Falls.

“They seem to like having a trillion or trillion dollar bill in their purse or wallet. We buy them for $1 and sell them for five. If they’re drunk we can get $10 a bill! Laugh and walk away.

In Mbare, US dollar dealers use loudspeakers to promote their businesses on torn bills. Only crisp notes are accepted here, so they buy damaged ones at a lower price.

But black market currency traders are at the center of a crackdown by authorities, eager to shore up the new currency that officially entered circulation this week.

Ironically – as with everyone who finds themselves on the wrong side of the law in this country – the more than 60 forex traders arrested last week had to post bail in US dollars.

Do you want a house? You must pay in US currency.

School fees? US dollars. A colleague told me that four of his grandchildren, aged between eight and 18, have not been to school since January as the family cannot raise the money.

A car? American currency please.

Rent? A new Zimbabwean passport? All American currency.

And how is this possible? Most of the nation survives on remittances.

Daughters and sons who joined a massive brain drain and moved around the world to work and transfer US dollars to struggling families.

“It’s incredible. It’s like we’re on a hamster wheel,” an economist told me, who asked not to be named.

“The same mistakes, another currency that no one knew about before its announcement. And yet the country has no productivity.

“Even the gold they pegged it to can’t be mined fast enough because most of it is being stolen,” he said, referring to allegations that large amounts of gold were smuggled out of Zimbabwe by people linked to senior government officials .

“This is miracle money, printed and not made, and therefore useless,” said the economist, who once worked for the government.

He explained that civil servants are paid part of their salary in US dollars and part in local currency, if applicable.

“It was a struggle and a mess. Show me someone who gets paid on time and I’ll buy you a whiskey,” he added.

Many citizens, desperate to escape this disaster, cross illegally into South Africa in search of an elusive and economically sustainable future.

There are two economic realities at play in Zimbabwe though: in the wealthier northern suburbs of the capital, you’ll find malls with Belgian chocolates, international wines and extra-large cheeseburgers, where no local currency is needed.

image source, You will do Sevenzo

For everyone else, Zig Notes will become a reality. A local ice cream vendor told me that a customer gave him his first note on Friday afternoon.

“I still don’t understand Zigs, but if I see them in circulation I’ll use them. There’s no way we won’t all have access to US dollars,” he said.

But like Ms Dhliwayo, he is not happy and does not trust the notes to retain their value.

The gardener agreed: “It’s like newspaper. It won’t last.”

And some are making the inevitable jokes about how the name sums up this country’s zigzagging economy.

Others in Harare have adopted the vernacular and say Zig means “Zimbabwe i gehena”, which means in Shona, “Zimbabwe is hell”.

Farai Sevenzo is a freelance broadcaster and filmmaker based in Harare.

You may also be interested in:

image source, Getty Images/BBC

#Zimbabwe #zigzagging #currency #chaos #BBC #News